VISIT OUR VIRTUAL TOUR FOR THIS EXHIBITION

Karen Duncan began collecting simple house forms more than fifteen years ago. “I don’t know,” she says, “I guess, for me, they symbolize security…memories of my youth…family.”

Over the years, the Duncans have assembled a diverse collection of sculptures and paintings in which shapes of dwellings make symbolic references. There are a few such geometric forms in the Kathryn and Marc LeBaron Collection, but they weren’t acquired as a specific compilation of houses. Instead, they were drawn by content, color, composition and other attributes as varied as Pablo Lopez Luz’s photographs of Mexican garage doors to Doug Dubois’s grandmother sitting on the steps of her home in the dying coal town of Avella, Pennsylvania. As Thomas Wolfe so eloquently acknowledged, “there is something in us all that seeks the warmth, comfort and familiarity of home.”

We are grateful to Karen and Robert Duncan, along with Kathryn and Marc LeBaron, who so generously allowed the use of works from their collections. We thank all who were involved in the organization and installation of this exhibition and hope that our visitors will find their own memories in the works exhibited here.

Exhibition Statement

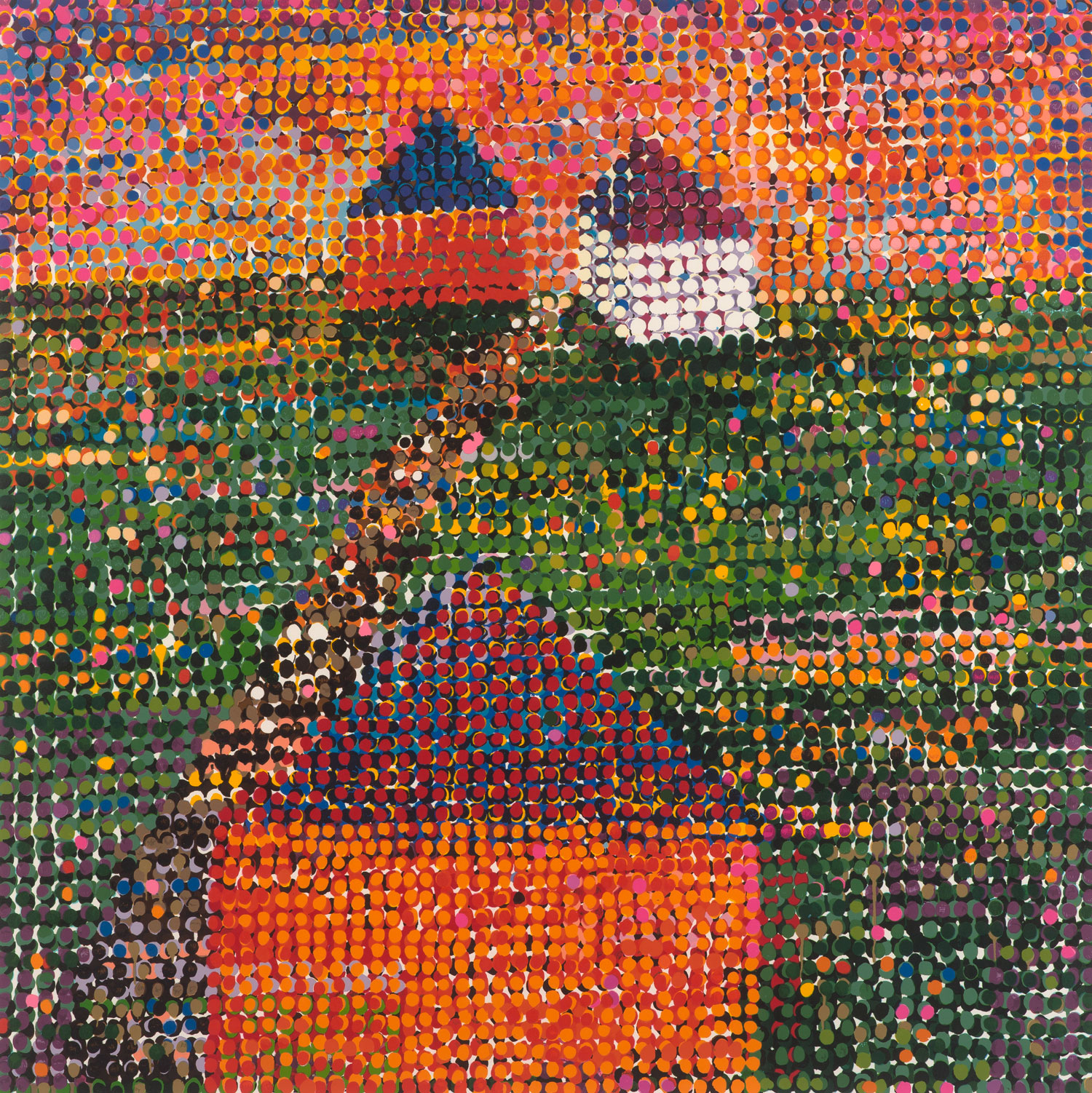

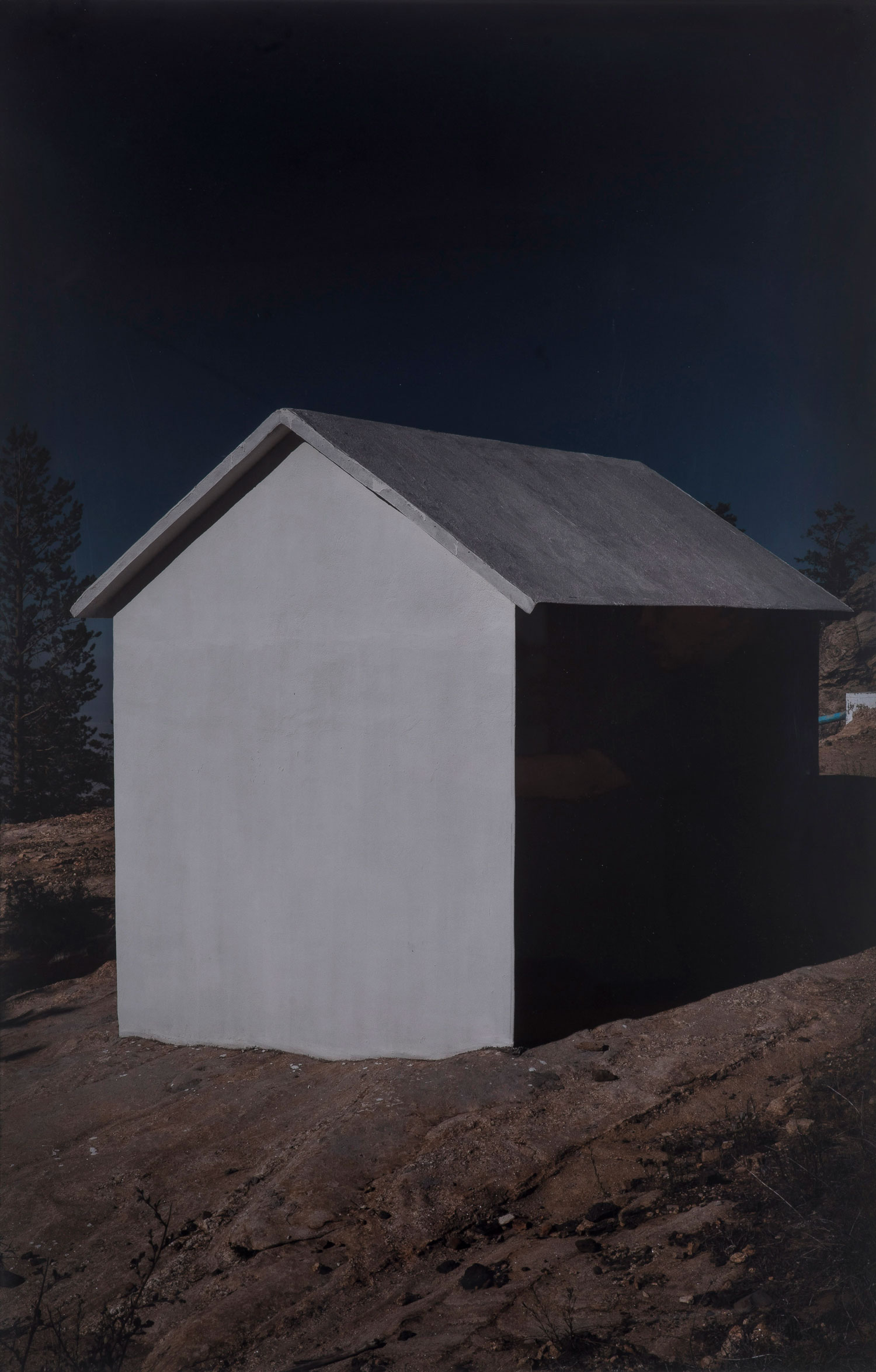

It’s a deceptively simple shape…a triangle atop a square…but it portrays, in essence, the anchor of our stories. Even the most minimal house form can hold references to dreams, longing, aspiration, fear, construction, destruction, wealth, poverty, life or death.

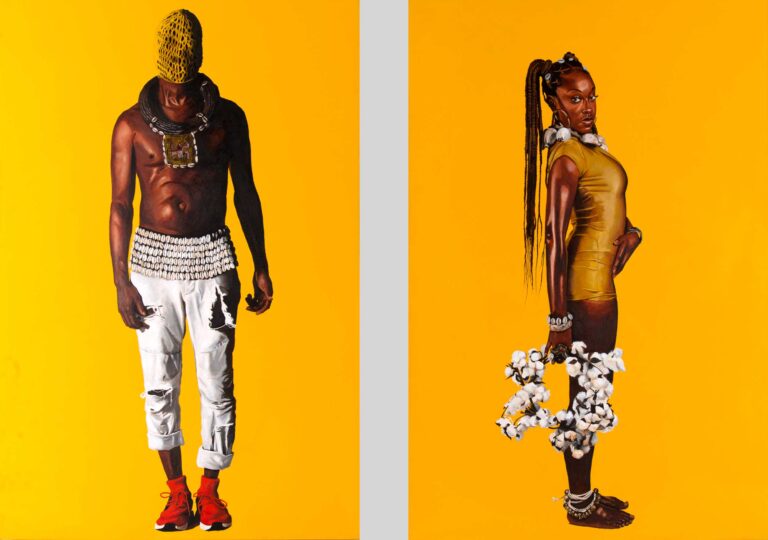

They carry cultural overtones, such as the suggestion of the house as a woman’s domain. Karyl Sisson’s works integrate materials reminiscent of her childhood home, such as zippers, buttons, bobby pins and hair curlers. Her Hut is constructed of clothespins. The patterning and intense repetitive labor required in the sculpture’s construction parallel the material’s function.

Merrill Peterson’s Portrait of a Chair and House poses questions of expectation versus reality. Here, we see an image of a chair and what is ostensibly a painting of the chair, as well as a painting of a house and the same house as seen through a window. As the viewer begins to discern that the neighboring house has no landscaping or similitude of the probable scene, a game of observation, perception and differentiation ensues.

While house forms generally convey a sense of warmth and security, the works of Jose Luis Cuevas, Hoss Haley and Xawery Wolski seem impenetrable. They are reminders that houses can imprison as well as protect. Mildred Howard’s bottle house is complex and multidimensional, yet it incorporates variations of a simple house form that references her personal experiences. She grew up in a redlined zone of Berkeley, California. Here, she includes evil averting bottles to deal with that memory.

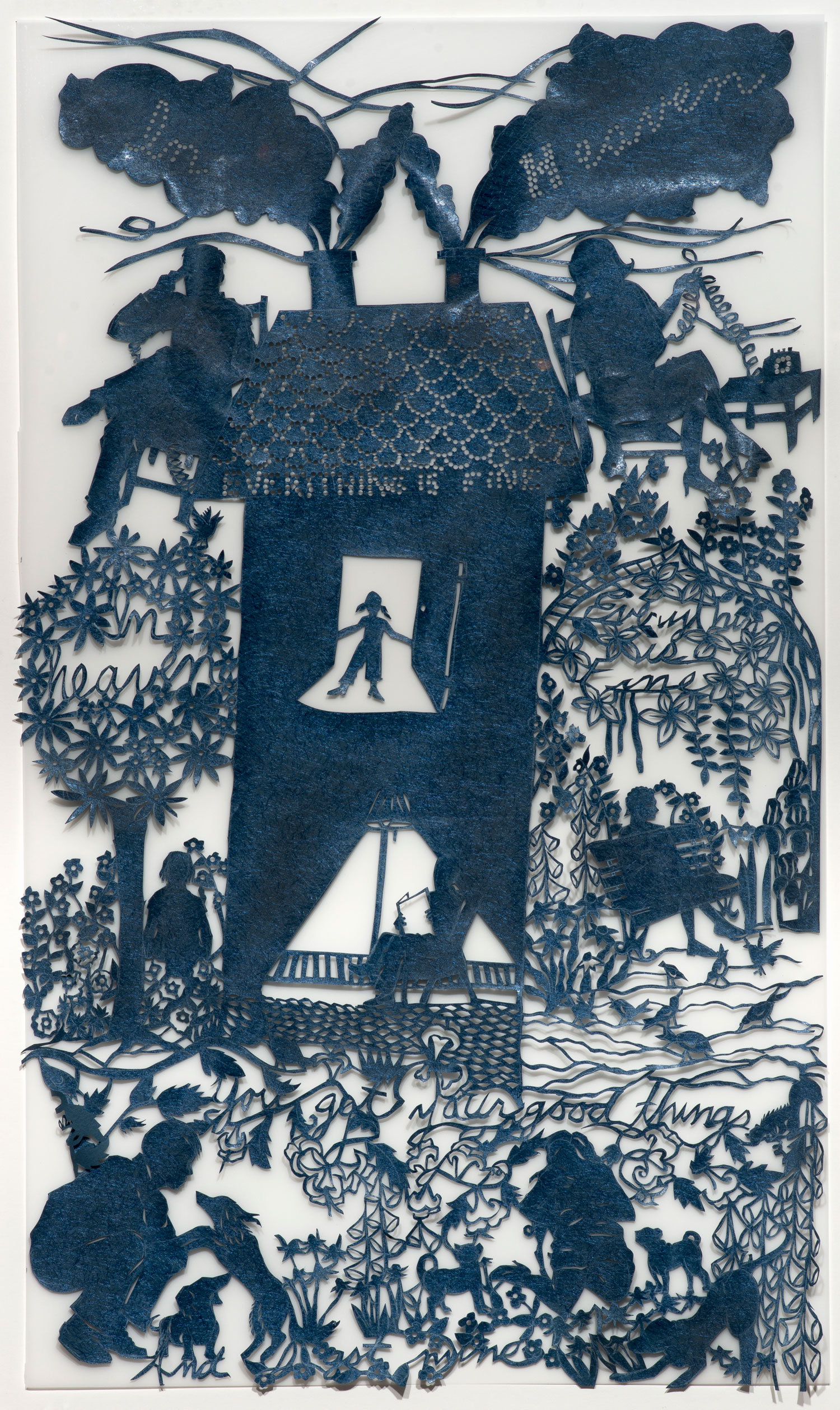

Abandoned, by longtime New York resident, Sandra Osip, is the portrayal of grief the artist experienced when she visited Detroit to find her childhood home gone and her neighborhood replaced by weeds, trash and nightly violence. The past and the future are central to cut-paper works by Sandra Williams. In heaven everything is fine portrays her in her house surrounded by the beloved dogs and relatives that have gone to their greater glory.

Characteristically, Williams ensconces the scene in a lush garden, as a reminder that humanity and nature are interdependent and both must be tended.

During her youth, Beverly Buchanan often traveled with her father, who was the dean of agriculture at an all-black college in South Carolina. These journeys fostered an interest in Southern culture and vernacular structures. Initially trained in health care, Buchanan eventually abandoned the field to study at New York’s Art Students League and Columbia University. While her work deals with issues of discrimination, poverty, civil rights, race and gender, her positive, indomitable nature made room for levity and optimism in the shacks she crafted of scraps.

An element of that notion is also present in William Christenberry’s images. He had a rare talent for photographing Alabama’s existing dwellings of tenant farmers, rural businesses and churches as though they were already part of a depressed and meager past. Yet, these images possess a degree of dignity and humanity. They suggest — as do others in the exhibition — that assumptions can’t be made about the happiness quotient within any domestic structure.